Entfremdungseffect

Exhibition

Galerie EIGEN + ART LAB, Berlin

15.11.2012 – 02.02.2013

Opening: November 15, 2012, 5 – 9 pm

“To alienate an incident or a character means to take from

that incident or character what makes it obvious, familiar or readily

understandable, so as to create wonderment and curiosity.”

(Bertolt Brecht, 1939)

It is one single word that underlies and connects the most recent works

by Ukrainian artist Lada Nakonechna: estrangement, or Verfremdung

in German. At first glimpse, her large-format pencil drawings Constructing

the new landscape (2012) as well as the associated video work in

the first room of the exhibition show landscape scenes and cloudy

skies, harmonic and overwhelming, following the tradition of 19 thcentury

Romanticism, but at the same time, an approaching break in

the weather is lurking through the dark clouds, a menacing disturbance

of the peaceful idyll. This comes down radically and abrupt in

every single work: a second image cuts in from the bottom, parts the

naturalistic scene in two with a hard horizontal line and overlaps with

the distant background. Instead, the bottom body halves of uniformed

policemen and protesters become visible, barrels and clenched fists,

banned on the sheet of paper by countless pencil lines, the meticulous

work of days and weeks. Like an image interference on TV or the

website that takes too long to load, one image slides over the first. But

neither the context of the individual scenes or the faces of the protagonists

become fully evident, nor do the images reveal their original

location. Following the Brechtian Verfremdungseffekt, Lada Nakonechna

uses estrangement to interrupt the familiar image, to destroy an illusion,

and to draw the attention away from the story told but towards

the observation of the means of telling and constructing it.

The term estrangement (Russian: ostranenie /ostranenie) was

already used by the Russian Formalist Viktor Shklovsky in 1914 to

describe a new purpose of art, which was to change the perception of

the world by showing its subjects in an estranged and alienated way.

Later, the term estrangement was also used by Brecht in German, and

was then misleadingly translated back into the Russian language with

alienation. In Ukrainian and Russian, there is only one translation

for the German words Verfremdung (estrangement) and Entfremdung

(alienation). Linguistic errors when translating German writers, like

Bertolt Brecht or Karl Marx, who crucially introduced the term Entfremdung

in the context of his critique of capitalism, are therefore guaranteed.

Lada Nakonechna uses this fact consciously by incorporating

another mistake when translating from German to Russian and back

again and lets Brecht’s Verfremdungseffekt change to Entfremdungseffekt.

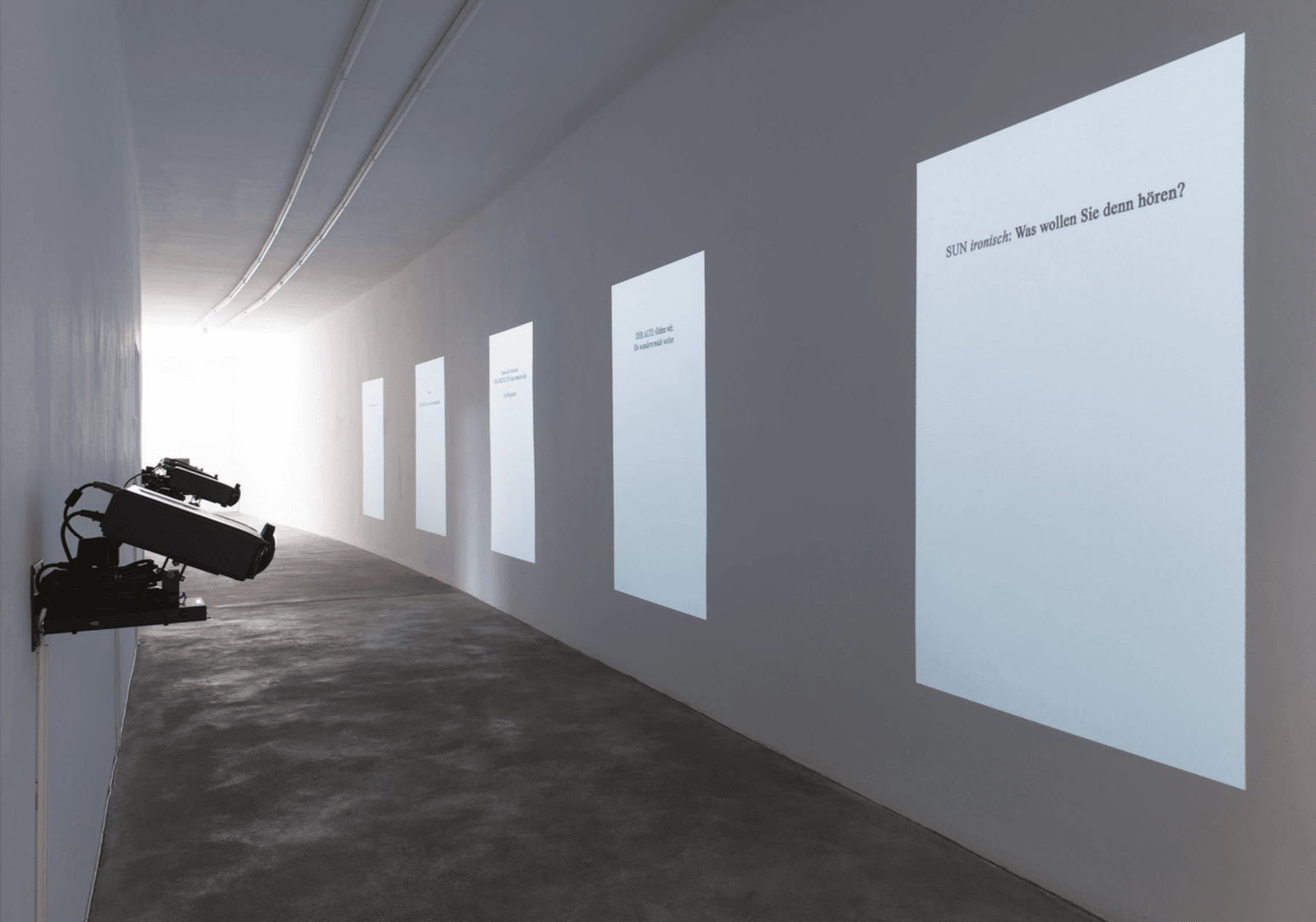

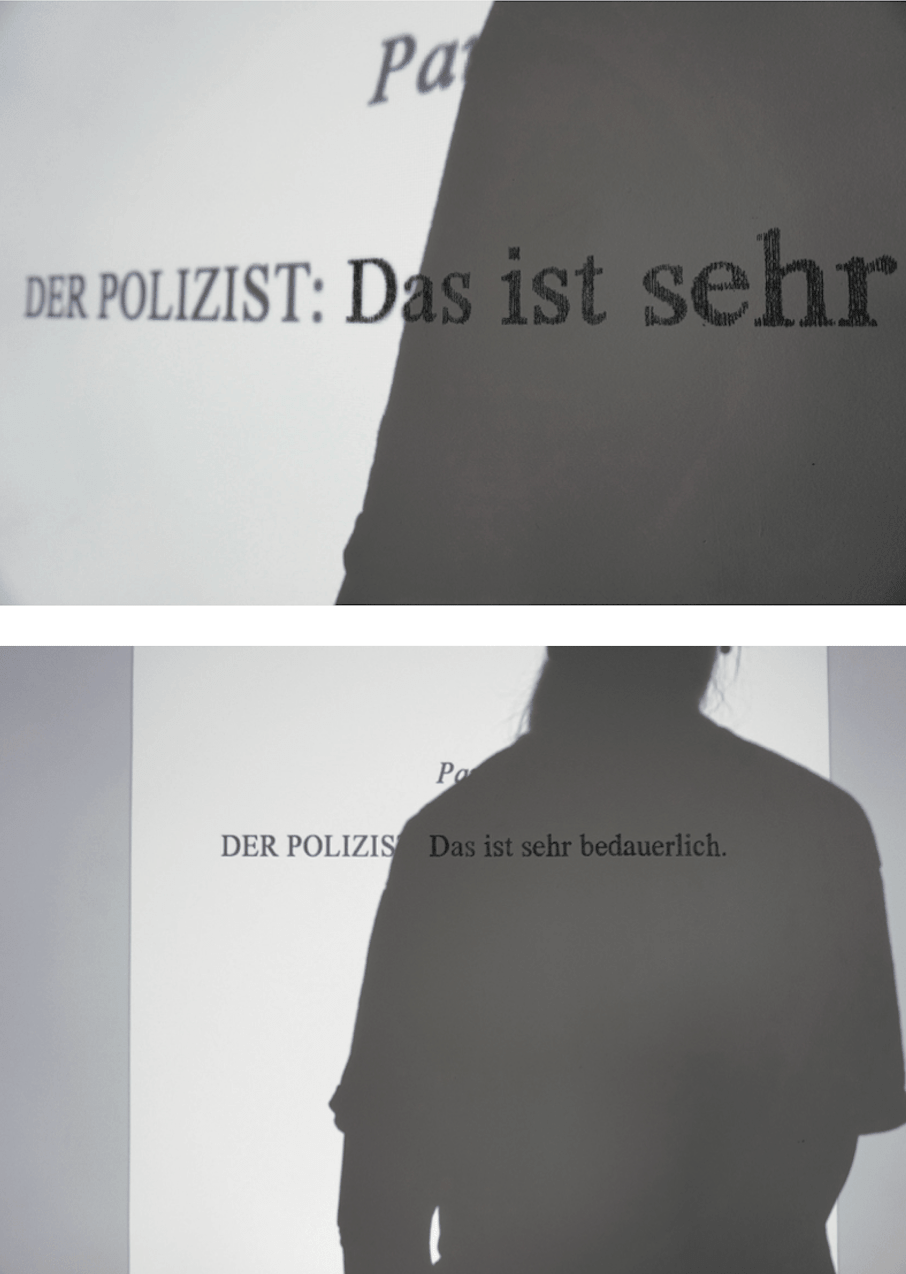

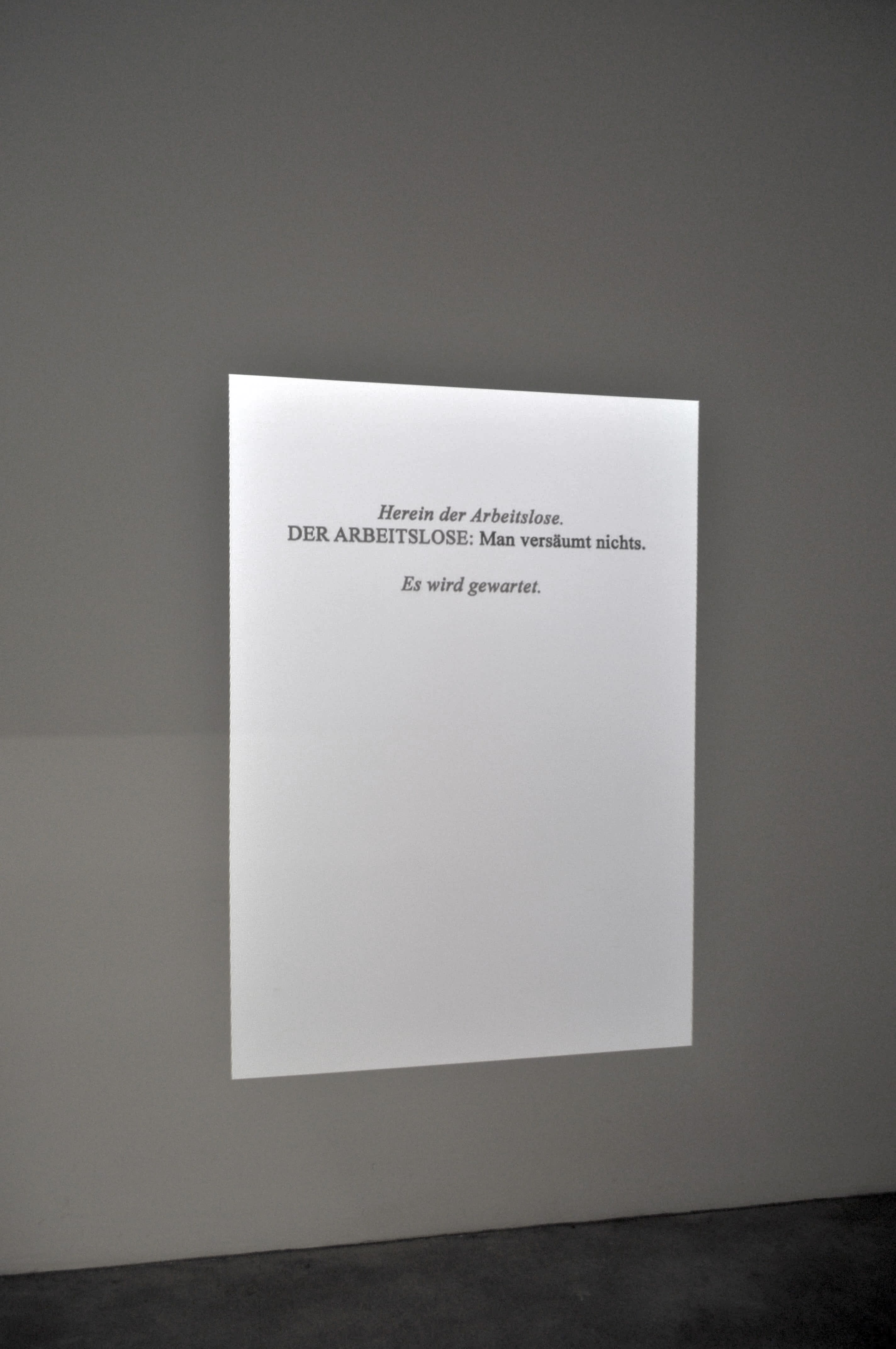

Per definition, alienation means to remove something from or disturb

in its accustomed place or set of associations. In consequence, the

viewer himself becomes a disturbing factor when following the logical

way through the corridor of the exhibition space, manipulating,

distorting and covering up the picture on the wall. The picture, in

this case, consists of quotes out of Brecht’s parable-play The Good

Person of Szechwan, a montage of two completely contrary narrative

threads – the ulterior world of the Gods and the banal everyday life

in a village in Szechwan (Appropriated phrases, 2012).

Already in a previous work from 2008, Lada Nakonechna used

singular phrases and words and estranged them into empty, cold

forms by removing them from their original context, but in the work

It’s been said before (2008), these were taken from soap operas on Ukrainian

TV. Now, the Brecht quotes stand as visual objects in the empty

space, they only exist through the light of the projector and are destroyed

by every viewer who faces them – and thereby alienated from

their original sense.

In the third part of the exhibition, the visitor is transformed from

being a passive spectator into forming a part of the image himself.

While the images were previously composed of scenes of protests and

riots taken from the media, overlaid by naturalistic views of nature,

the full image is now only partially predetermined by the room-sized

wall drawing Incomplete (2012) on the top half and ceiling and completed

on the bottom by the person of the viewer and his position within

the space. Instead of simply trying to activate the viewer to think

about the figures in the work and the prevailing conditions in reference

to the V-Effekt, he gets involved in the work by becoming part

of it and directly affects its outcome. When artist and viewer change

sides and the viewer gets involved in such a way in the work – a strategy

crucial for Lada Nakonechna’s works – then who is the recipient

of the message, sent off by the artist only as a first impulse?

The works in the exhibition shall not answer questions about how

methods and new forms of art are supposed to work, nor do they pretend

to be a new form of art. They only show the tryouts, sketches and

stages, which the artist undertakes in the search of it.

“It is for you to find a way, my friends, to help good people arrive at

happy ends. You write the happy ending to the play! There must, there must,

there must be a way!”

(Epilogue, The Good Person of Szechwan)

Leonie Pfennig

Incomplete, 2012

Incomplete, 2012

Constructing the new landscape, 2012

Constructing the new landscape, 2012